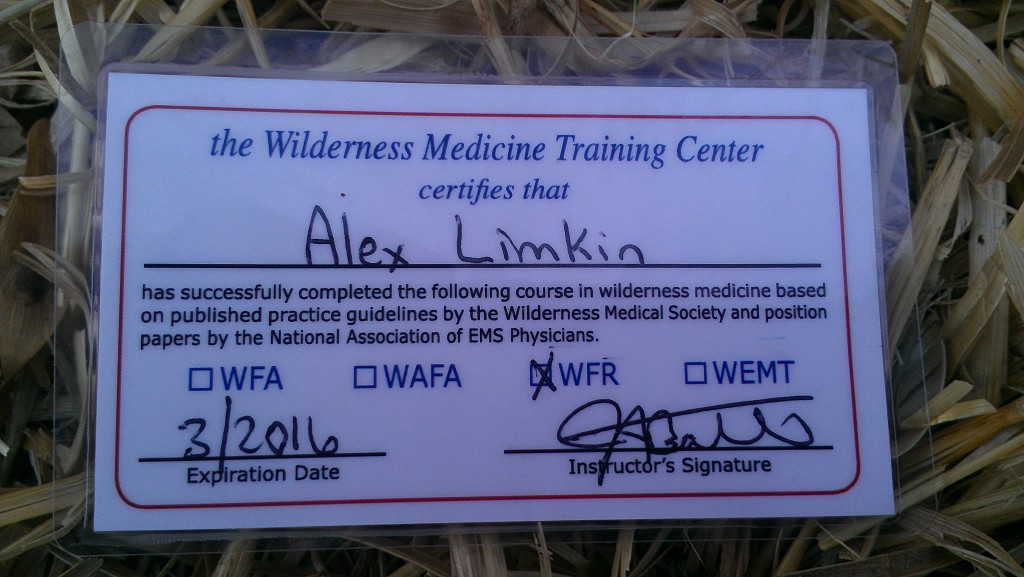

There were several reasons why I thought it would be a good idea to get my Wilderness First Responder certification. For one, I wanted to see what it would be like to learn how to save lives, as opposed to the opposite.

Secondly, I knew that any work involving distressed veterans running loose in the backcountry would be dangerous, and having this certification would likely be a prerequisite to work in the field.

And lastly, I spend so much time alone and out of contact in remote terrain, that the knowledge and ability to administer self-aid seemed really, really important.

Anyway, I was able to identify a program offered by the Wilderness Medicine Training Center and hosted by the Outward Bound School in Leadville, Colorado. It was a good choice. By day we did coursework and went through involved and realistic incident simulations outside in the snow.

By evening I skijored in the surrounding mountains with AB, returning by moonlight. .

AB feels comfortable in the woods, and I feel safe in the woods with her. It is only when she pulls up short, with her nose to the wind, that I stiffen. It is at these moments that a skier, alone in the dark with only his dog for company, can imagine, all too easily, something frightening. Although these were the same mountains that we had spent a week in during our Outward Bound Veterans Course the previous January (which I wrote about here), it only takes a small but noticeable hesitation on the part of AB to fill me with apprehension and dread.

“What is it, girl?” I would call out to her in these moments, in a voice filled with false confidence, at the same time taking a firm grip on my pole. After a moment of listening, it would often seem worse to remain still then to just press on ahead, no matter how blindly.

“Come on, it’s nothing, let’s go!” In this way we progressed through the snowy woods until we came upon the lights of camp.

Though the WFR training was hard, I made it through. I celebrated my completion of the training and my new certification by going up Monarch Mountain without climbing skins (because I didn’t have any). I herringboned my way to the top in a glassy stupor, pausing just long enough to shed layers as I overheated.

Coming down on legs of jelly I was appreciative of my life-saving training. I had a detailed waterproof (and tear-resistant) manual with me and two flexible SAM splints in the event that something went awry (and which I still carry with me on even short trips.)

As fate would have it, it wasn’t on my own person that I would first test my WFR skills, but on somebody else. And as fate would have it, it would be on the very same mountain where my life almost ended–in fact within spitting distance of the very tree where I had come to rest, grievously stricken and hanging on by a thread.

The only thing that could have made the day more extraordinary is if the victim had been the same person that rescued me: a vacationing Spaniard from Trujillo who served in the Red Cross. (In this instance, the victim was an Argentinian vacationing with his girlfriend.)

The first news of the accident was communicated to me by a frantic woman gesturing wildly from the lift as she passed overhead.

“Somebody just flew into the woods by Tower 3. They need help! Help him! Help!”

Many things leapt through my mind in this instant. The first was absolute horror. I felt I was reliving my own near termination: a sudden inability to breathe, the thunderous pain of a suddenly crumpled skeleton. The second was a sense of impossibility, that this couldn’t be happening to me, here, now, being called upon to help save someone in the same place that I had nearly died four years ago, someone who had also darted sparrow-like into a wood-filled oblivion.

I fought to suppress my immediate and overwhelming impulse to continue down the mountain and report the fall to the first aid station at the bottom of the hill, light up a cigarette, and just hope everything turned out okay for the guy.

But the thing of the thing was, I knew instantly that the right thing to do, the only thing to do, was to stop and render aid. What if the victim needed help in that very moment? What if an artery had been severed by a tree branch and they were bleeding out? What if I could rip the shirt from my body and create a pressure bandage? What if they were unconscious and vomiting and needed immediate assistance to keep from suffocating?

What if in the time it took for me to relay the emergency message to ski patrol, and for them to then dispatch someone to the scene, and for that person to figure out where they were supposed to go, etc. etc., something could have been done to save that person?

A life was at stake. That much was clear. And I was needed. I plunged into action, cartwheeling to a stop by the pair of lone skis just off to the side of Tower 3. The sight of the skis alone sent chills through my body. There was no one in sight and there were no tracks in the snow. He had evidently flown through the air into the woods, perhaps departing this world like a mad bird, like a doomed bird hurtling into a sliding glass door. I didn’t know how fast he had been coming, but fast enough that both skis had released nearly side by side. There was no time. In a single movement I released my bindings and kicked free of my skis.

I slipped down into the woodline frantically, knowing that somewhere in the shadowy darkness was a body, someone who could very well be broken and dying. There were no screams of pain or agony, no muffled stirrings. Nothing but silence and the sound of my boots scrambling to gain a hold on the slippery slope of ice and tree and rock. The only person screaming was myself, unconsciously, without thinking, as though it were somebody else in my body and not me: “MAN DOWN! MAN DOWN! MEDIC! MAN DOWN!” Between breaths I strove to listen, but there was nothing but a silence. It was the silence of true unabashed horror. A silence I knew well. Against my will I remembered my own fantastic agony, my own silence, unable to take in a single breath with my fractured sternum, unable to move a single fractured limb, unable to sob, unable to moan, unable to cast anything of myself about but my eyes, which were narrowed to tiny slits, the slightest of openings, which wanted only to escape my body, to escape everything, which had seen too much, envisioned too much, absorbed too much.

As I searched and scrambled over the rocky tree covered slope, I found myself in a delirium, preparing for the worst, and trying to shut the worst out of my mind. I could already see the body before me, limp and still, perhaps stabbed through the eye with a tree branch, through the brain, dead instantly, waiting only for me to squeeze my eyes against the sight of it and look away, turn insensible, collapse.

It may have only taken 10 or 15 seconds scrambling in the woods until I spotted the skier, but it felt like an eternity. When I reached his side I could see his face covered in blood, just as I had imagined. He was lying on his back at the base of a tree. I was relieved to see that he was conscious and appeared to be breathing. His eyes were open and moving around. But the sight of his bloody face and the gash to his forehead filled me with dread.

We had learned in WFR training that brain injuries are one of the most insidious and chilling injuries that you can ever come across, because their effects are deadly, and it is not always easy to diagnose them, even for professionals. For this reason, increased cranial pressure, or ICP, is often referred to as “parking lot death,” because the injured person may appear well enough to be released, but then keel over dead without warning just a short time later. ICP was the deadly and often quick build-up of pressure in the brain from head trauma, i.e. striking a tree at high speed with your head, doing a header into the woods, breaking a tree in half and being in turn quartered and splintered which is what could have happened to this guy, easily could have happened to this guy.

Because of his incoherence, and his inability to answer questions or take direction, and because I didn’t know with what velocity his head had been impacted, I immediately suspected the worst. Over and over he kept mumbling, “What is happening to me? Where is my girlfriend? Has my girlfriend been hurt?” I kept his head and neck stabilized against the uneven terrain, just as I had been trained, and did a blood sweep with my free hand to check for additional injury. I reassured him in his native tongue. I continued with my assessment. He kept asking the same questions. It was at this time that the first ski patrolman arrived on the scene.

He observed the steepness of the terrain and backed away, saying something about approaching us from a safer direction.

Way to go Alex!!! Nice to see you using the skills we learned and overcoming your past to do it. Give AB a hug for me.

Wow! You need to send this to Dick Kniffing