“Hey, take a picture of me taking a dump,” Paul said.

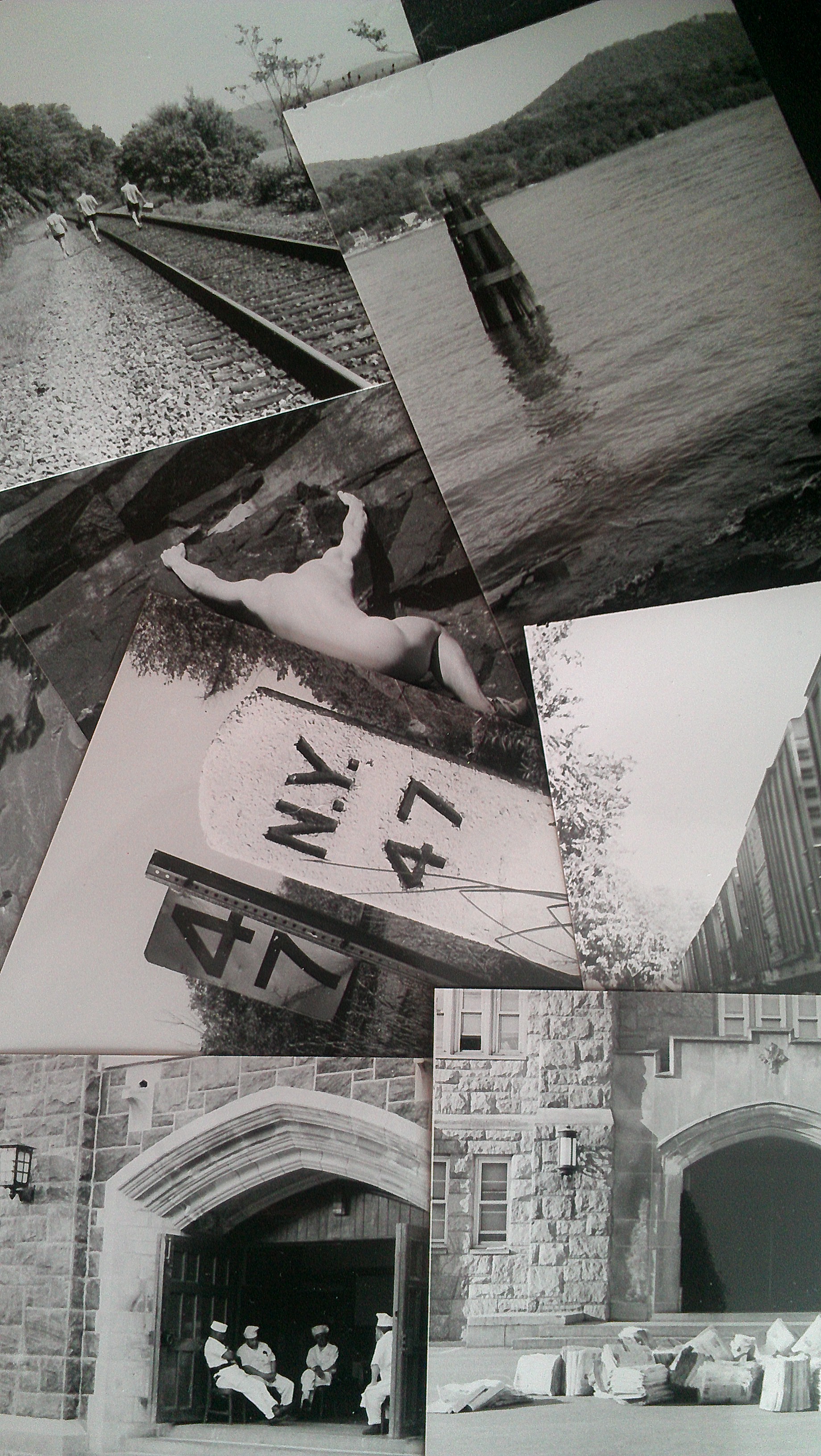

We were down by the Hudson River at the Joint, climbing around on the black cliffs that went up 100 feet or so from the banks of the river to the road above.

It was late summer 1993 and we were 21 year-old plebes at West Point. We could drink but we had no booze, drive but we had no car. So we monkeyed around down by the river, as far away from the grounds of West Point as possible without being considered AWOL.

Paul had an 82nd Airborne combat patch and a Combat Infantryman’s Badge (CIB) from Desert Storm, which made him hotshit at West Point, kind of untouchable, whereas I had been an intelligence weenie, which subjected me to additional hazing. The truth is I coveted the CIB on Paul’s chest, knowing what it would have meant for me there at the Joint. Just one look and people gave him a wide berth.

Paul didn’t talk much about his CIB other than to say they gave it to him for seeing some dead bodies on the highway, people that had been cooked. He was kind of dismissive about the whole thing, about the CIB, about Desert Storm.

I don’t know why I had a camera with me but I did.

“Okay,” I said. “Do you want just the one, or kind of like a sequence?”

I had not yet taken a photography course but it was something I wanted to do, only I knew it would never happen there. Not at the Joint.

“Do like an action sequence,” he said.

I assumed he was going to boulder up to some spot he had picked out and then strip down. I don’t know why I thought that. I guess it struck me as somehow more seemly.

In actuality, it made more sense to strip down and then climb up, which is what Paul did, leaving on only his shoes.

I tinkered with the camera to avoid having to watch.

Out across the river I could see two sailboats making their way upstream. I wondered who was on board. Every now and then there were girls in bikinis.

It was my fantasy to swim out there, have sex with the girls, and never come back.

“Now watch where you’re standing,” Paul said as he began climbing.

“Don’t worry about me,” I answered, still looking at the boats.

Paul found a nice bucket hold about 20 feet up and squatted in against the cliff.

“Okay, you can start shooting already.”

I could hear a change in his voice from the effort.

“Man, don’t pop a blood vessel.”

I found myself grateful for the camera. Somehow it was easier to observe the whole thing through a viewfinder, as though I wasn’t really there. It helped that I had to manually focus the lens. It gave me something to do.

Paul’s shit was incredible and disturbing. It grew longer and longer until it finally resembled a tail.

“I can’t believe it’s not breaking off,” I said. “It’s like a snake escaping from your ass.”

When Paul laughed, the tail, which was easily two feet long, broke free. I clicked the shutter, catching it in freefall.

I guess I should have been more worried about Paul, even though he was the one that went on to graduate and I dropped out after a year, flipping burgers at the McDonald’s in Highland Falls outside the gates of West Point to earn gas money home.

Three years later he was a new lieutenant attending the Air Defense School at Fort Bliss, and I was completing an English degree on the G.I. Bill in Las Cruces.

It was only about 60 miles away so I drove out to see him.

Paul didn’t look well. A couple hours into the visit, while we were driving to get some food, he confessed he was taking anti-depressants and seeing an Army shrink. It all seemed pathetic to me. That he had signed up for Air Defense also seemed pathetic. The whole visit was depressing. I felt sorry for him and didn’t want to be like him. That was the last time I saw Paul.

The next year I reported to Fort Benning for IOBC and Ranger School. I was going to be a killer after all. Next stop was the Republic of Panama and a penthouse in Punta Paitilla. I forgot about Paul, forgot about the big turd he dropped off the cliff at West Point, and about the bodies he saw burned along the highway in Desert Storm.

When my turn came, I went to Desert Storm 3.

Now I got me a war badge, too.

Perhaps your friend didn’t look well in relation to your distance from him. You seem to be of a different cut than him, more sensitive and introspective. I think your humanity will be your salvation.