Legend has it that two great principalities had been at war for a very long time in ancient China. Many people were killed. Slaughter was widespread. Many hoped for peace. Many prayed for peace. Humble candles were lit under thatch roofs before altars bearing momentos of the fallen.

On her eighteenth birthday, the daughter of one warlord, Ying Li, knowing that a request on her birthday would carry special weight, implored her father, Hang Man, to seek peace because she could not bear the wanton destruction of precious life. Her own brother, whom she loved dearly, had been killed in the fighting.

The potentate, who loved his daughter—but thought her weak and not capable of rendering serious advice on war—realized that it would not do to put her off entirely. So he came up with a plan.

He decided to invite the other principality to send twelve ministers to have a peace discussion. Without telling his daughter, he made it clear by messenger that these ministers, whoever they might be, were not to come bearing bladed weapons of any sort: “no jian, no willow leaf dao, no goosequill dao, no liuyedao, no wodao, no zhanmadao, no yanmaodao, no katanas, no darts or throwing stars, no bladed weapons, get it!”

It was his belief that this invitation would not be accepted. By dictating that no bladed weapons were allowed, it was his feeling that his counterpart, the Fukien leader Zhen De, suspecting fowl play, would decline the invitation. His daughter’s request would be acknowledged. War would rage on.

The Fukien leader, upon receiving the invitation, did suspect the possibility of fowl play. But he believed there were ministers among his crew that were willing to risk themselves for peace—no matter how small a chance was theirs to achieve it.

He was honest with them when they assembled in the great hall.

“Ministers, I believe there is great risk in agreeing to attend this peace convention. Hang Man has made it clear that bladed weapons will not be permitted. I can only assume that he wishes you to be defenseless.”

At this there were glances and a few murmurs among the ministers.

“But since there is a chance at peace, even though the invitation is irregular, and smells of subterfuge, I thought it prudent to bring it to your attention. If after three days of debate, there are twelve among you (at this point the Fukien leader faltered in his speech for he knew the courage of his ministers, having been one himself) that will go on this dangerous mission, you will have my blessing. I will not order any one of you to go, nor will I assign a minister to make this decision for me.”

At this the meeting was adjourned.

Legend indicates that the turnout among the ministers was indeed overwhelming. Because there were so many volunteers, it was impossible to decide on just twelve. Hong Bao, one of the wisest ministers, proposed a solution.

“Seeing as our delegation may only consist of twelve ministers, and these twelve must go without bladed weapons, and because we know that this restriction will serve to render us vulnerable to attack, it is my suggestion that we send those among us who are most skillful in the use of our non-bladed weapons: “the yuetong, the sanhue, the xilili, the renminbi, the galang, the vietcong…Am I forgetting anything?” One minister gestured to the simple wooden cane that Hong Bao had taken up following a fall from a house.

“Oh yes,” Hong Bao chuckled. “This, too.” He raised the cane and shook it like a rattle.

The other ministers were unanimous in approving this idea.

Three days of nonstop competition among the ministers produced what everyone believed to be their twelve best. It came as no surprise that Hong Bao, old as he was, numbered among the twelve.

Rising early in the morning, the twelve breakfasted and departed on foot.

When news arrived that the delegation was approaching, the potetate/emperor/warlord Hang Man was both baffled and dismayed.

“But is it confirmed they have no bladed weapons among them?!” he insisted.

“Yes, my lord,” reported the leader of the scouts who had been observing the Fukien ministers for the last week as keenly as a hawk. This scout leader was known as Pin. Pin was widely trusted and respected as a skilled fighter and honorable man. One of the reasons he had been assigned to the scouts was that the emperor secretly wished him dead—because Pin was growing in popularity. It was just a matter of time before the emperor found a reason to send Pin on a mission from which he would never return, a thought the emperor turned to whenever his spirits needed brightening.

“The Fukien ministers are none of them carrying bladed weapons,” repeated Pin, trying to find the right combination of words that could communicate his findings.

“Hummphh,” said the emperor, as though the absence of bladed weapons were Pin’s fault. “We will greet them properly as guests, allow them to spend the night unmolested, and then in the morning, attack them at the breakfast banquet. I will be seated above and…”

“I’m sorry, my lord?” said Pin, unsure of what he was hearing.

“Oh, you are still here? You’re dismissed.” The potentate made a gesture with long curving nails that he believed, proudly, to be especially grotesque. Simple Pin knew nothing of soliloquys.

Pin hurried away, unsure of what he had heard. “It can’t be true,” he thought to himself. “After all, the Fukien ministers have come per his bidding, they come unarmed, it would not do to attack them. I must be wrong. I must find out more.”

Pin’s father-in-law was a high-ranking official with his fingers in just about everything. It was to him that Pin turned.

“What you have heard is true,” confirmed his father-in-law over a bowl of noodles. “We are preparing for the worst. We believe that the emperor intends to kill all the Fukien ministers. But since we are already at war, it does not seem that this will likely make much difference in our relations with the Fukienese people.”

“But it makes no sense!” Pin exclaimed. “The emperor could just as easily fiddle them for three days and send them on their way. Why kill them?”

“To save face, of course,” said the father-in-law, surprised at Pin’s simplemindedness.

He saw an explanation was necessary: “The arrival of the Fukien ministers, unarmed, is an indication they have little respect for the emperor. If they respected him, truly respected him—feared him that is—they would arrive with concealed bladed weapons, just in case they ran into problems.”

Pin shrugged his shoulders. It made no sense. The Fukien ministers were walking right into a trap. They were to be killed, slaughtered. There was no sense to any of it.

In his defense, Pin had no idea of the peace request that Ying Li had made of her father, which explained much.

Pin could not sleep that night. He finally got up and sat in the garden. “This emperor makes no sense,” he thought. “Where is the sense in inviting a delegation of peace and then killing the delegation…? Not only is it wrong, it is…dishonorable.”

With this word, Pin sprung to his feet, as though confronted by a phantom tiger.

If the plan was dishonorable, and he knew of the plan, what was his obligation, what his duty?

A chill ran over his body.

He looked at the sky. It was only just starting to lighten. There was still time.

Pin ran to the armory in the basement of the emperor’s palace, where the most valued bladed weapons were kept, those that had been handed down through the ages, whose blades had glistened under every type of moon with every kind of blood, and he made a request of the armorer.

“I need twelve weapons folded up in a carpet: six jian, a willow leaf dao, a goosequill dao, a liuyedao, a wodao, a zhanmadao, a yanmaodao, and if you’ve got any throwing stars back there, give’em up.”

The armorer, who was a little blurry at the early hour, complied dully.

Pin arrived at the banquet hall bearing the large and heavy carpet as inconspicuously as possible. He called out to Hong Bao just as the Fukien ministers were seating themselves at breakfast.

“Hong Bao, I am Pin. I have something I would like to give to you.” Then he gestured with his eyes as though to say, “If it please you, I think we should continue this conversation under the table.”

Something in the voice of Pin called out to Hong Bao. He coughed and bent down, pretending that a pebble in his shoe was troubling him.

Under the table, Pin produced the six jian, a willow leaf dao, a goosequill dao, a liuyedao, a wodao, a zhanmadao, a yanmaodao, all carefully wrapped in a carpet.

“What’s the meaning of this,” whispered Hong Bao. “Is it what I think it is?”

Pin nodded gravely.

“You are short qian (money) and need to sell the carpet?”

Pin smiled sadly. “The other thing.”

“And you are truly named Pin?”

“Yes—to do something as though your life depends…

“Yes, I know what your name means.” Hong Bao reached into the carpet and cradled the hilt of the willow leaf dao with his good left hand. He favored the willow leaf dao but knew from experience that the liuyedao was also an attractive option. Knowing that there were only twelve weapons, he took up his wooden cane, which had never left his side. Pin understood.

From under the fringe of the banquet hall linen, both Pin and Hong Bao could clearly see scores of feet and legs coming into view and moving into position. It was the feet and legs of many armed soldiers. There was a clanking of weaponry and whispered commands. It was evident that thing were indeed unraveling.

After a moment in which neither man said anything, Hong Bao took his other shoe off and said a short prayer. Then he said another shorter prayer for his men. It was now just moments. They had just moments.

Hong Bao clutched at the younger man’s arm: “Pin, you know your actions will never be forgotten. Do you know this?”

But Pin was already out from under the banquet table.

In what seemed like a single movement, he deftly shook the carpet with his left hand, releasing the remaining weapons to the other ministers who had joined him atop the great table—while simultaneously helping himself to a jian in mid-air with his right.

Though they fought bravely, all were killed. In the aftermath of the fighting, Hang Man, believing that he would never secure the adoration of his daughter if he maintained his bloodthirsty ways, begrudgingly entered into a peace with the Fukienese people that lasts to this day.

As with the Fukien ministers, the life of Pin has not been forgotten. Many parents still tell their children, “To accomplish something, anything, all you need is a simple Pin.”

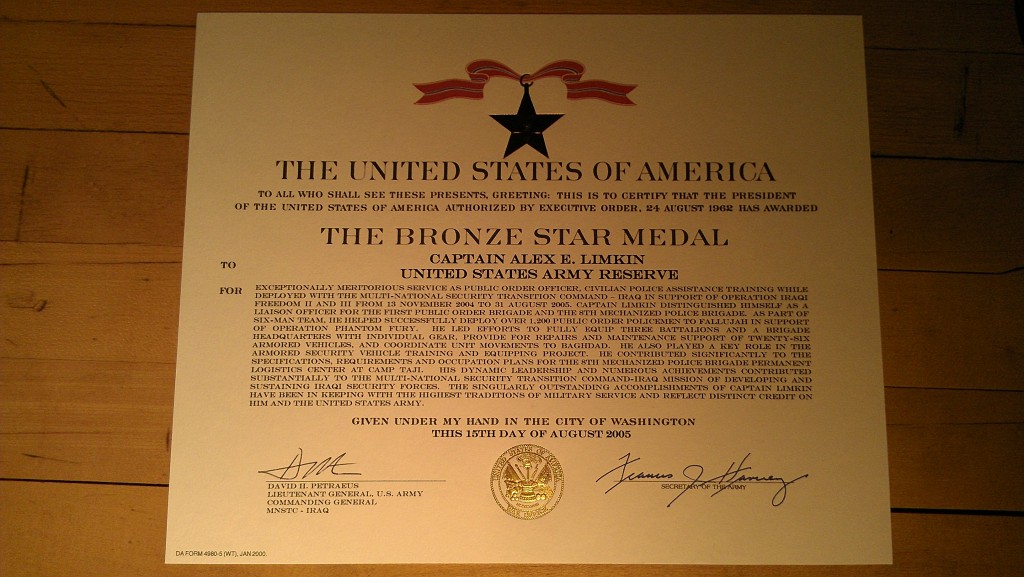

Dedicated to my fallen commander and fellow Ranger, Colonel Theodore S. Westhusing